The Man Who Killed Halloween…

November 16, 2021

*Credits to Vice.com for all information*

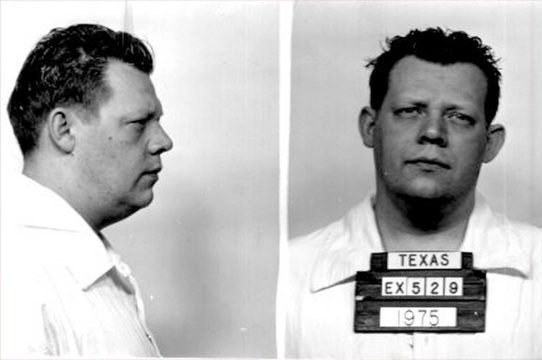

On a rainy Halloween night in 1974, streets in Deer Park, Texas were filled with trick-or-treaters. Among those people were optician Ronald Clark O’Bryan, now widely known as “Candy Man” or “The Man who killed Halloween” watching over his children. The two kids were eight-year-old Timothy and five-year-old Elizabeth as they were going from door to door through their neighborhood. Accompanying them was their neighbor Jim Bates, and his young son. As they were walking by they saw a house with no lights on. The vague possibility of getting candy was so enticing that they knocked on the door.

There was no answer. Either the resident of the home was hiding inside, or simply wasn’t home. With their levels of patience slowly decreasing the kids just decided to go on to the next house, and Jim followed them. The only person who stayed behind was O’Bryan all alone by the dark house. A little while later O’Bryan had come bearing “good” news. He had pulled out a handful of 21-inch pixy sticks, which are little paper tubes filled with colored sugar. Turned out somebody was home. Ronald Clark O’Bryan was apparently given a handful of sticks. Each child received a stick including O’Bryan’s kids and a 10-year-old boy he had recognized from the church as they were walking home.

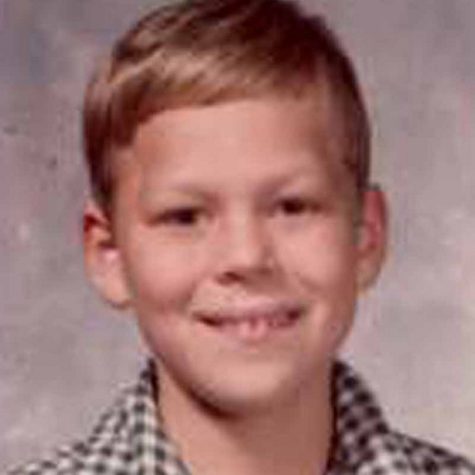

Before bed that night, Timothy O’Bryan was allowed to eat one treat from his Halloween haul. The young boy had been wanting to eat the pixy stick since he received it. But the stick wasn’t easy to open. And the reason was because it was stapled shut. After his dad helped him open the stick, he was able to take his first mouthful. Timothy said it was bitter and just tasted really gross overall. O’Bryan gave his son some Kool-Aid to wash the taste down. And just like that, in less than an hour, Timothy had taken his last breath.

According to Vice.com, “It was just a coincidence that I was working the police intake that night,” says former Harris County prosecutor Mike Hinton, decades later, on the phone from Houston. “I got a call from the Pasadena police department—they told me an eight-year-old boy had died. He was rushed to hospital, but he’d already passed.”

Eager to start the investigation of the case, former prosecutor Hinton called Dr. Joseph A. Jachimczyk, chief medical examiner of the nearby community of Harris County. “I told him the situation and he asked what the young man’s breath smelled like,” says Hinton now. After calling the morgue it was concluded that the young boy’s mouth held a vague scent of almonds. Dr. Jachimczyk declared that the smell was coming from cyanide. The examiner’s hunch was proven by an autopsy. A pathologist had concluded that Timothy had consumed enough Cyanide to kill two people. Through testing, it was later discovered that the first two inches of the Pixy Stick were made up of cyanide.

The police were able to track down the remaining tubes from the other children before they were in the position of unknowingly poisoning themselves. It was noted that whoever was responsible for Timothy’s death stapled the Pixy Sticks shut after tampering with them. Hinton recalled saving another boy’s life that night. “They found him in bed with the sweet in his hand, but he wasn’t strong enough to undo the staples.”

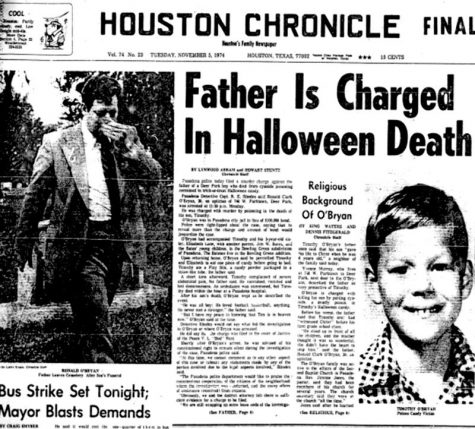

The police asked Ronald to lead them to where he had received the toxic sugar sticks. But Ronald couldn’t find the house and claimed he didn’t see the possible criminal. The investigators began growing suspicious. “A few days went by, and it was incredibly frustrating,” says Hinton, “so they took O’Bryan out again and were pretty firm with him.” Their tactic worked and O’bryan’s memory was back up again. He led the police to the house.

The man who resided in the house wasn’t home, so the officers went to his place of work. At Houston’s William Hobby P. Airport, and his colleagues saw him get arrested with their own two eyes. Everyone thought the mystery of the poisoned pixy stix would be over, case closed. There was one thing that prevented that from happening, the accused’s alibi. The man had been at work the night of Timothy’s death. His wife and daughter had turned in for the night early, as they ran out of candy. Witnesses, the man’s colleagues, and timesheets had proven the man’s claim .” This only magnified my suspicions,” says Hinton. “I’d also heard O’Bryan was angry at his relatives for not staying up the night of Timothy’s funeral, which was odd.”

Ronald had written a song about Jesus, and how his son Timothy had joined the Lord in heaven. He had grown frustrated with his miserable, grieving family when they refused to stay up late to watch a recording of the performance, which at the time was broadcasted on television. “Something strange was going on,” says Hinton.

A little later, while Hinton had been educating a class of future officers at Pasadena Police Academy. When detectives arrived at the door. They discovered that O’Bryan had recently taken out life insurance policies on his children. In January he had taken out $10,000 per child and doubled the amount each in September, a month before Halloween. He had accumulated a total of $60,000. The investigators had known in advance that O’Bryan had unresolved debts which amassed to over $100,000 dollars. When they found out that

he had called his insurers inquiring about payout the morning after Timothy’s death at 9 AM, the evidence against him was finally starting to merge together.

Granted a search warrant, A search occurred in the O’Bryan household. It revealed a pair of scissors coated in plastic residue, which was oddly similar to the residue found on the poisoned packed candy. The Candy Man was arrested and taken in for interrogation. As the investigation continued more and more of the found evidence was pointing towards O’Bryan. “It turned out O’Bryan was going to community college and in class would ask his professor questions like, ‘What is more lethal: cyanide or another type of poison?'” says Hinton. “Why would someone ask that?”

Another witness in the case, who had worked for a chemical company in Houston, had told officers of a man who came in, with the notion of purchasing some cyanide. The man disappointingly left after hearing the maximum amount he could receive was a mere five pounds. The worker couldn’t confirm that the potential buyer was the suspect but could remember that he was wearing blue or beige medical scrubs. Scrubs were what the Candyman was wearing to work.

This all happened before DNA testing and contactless debit cards. The police couldn’t confirm that O’Bryan was their criminal, and also couldn’t confirm his alleged appearance at the chemical company. Prosecutor Hinton, remembers the now well-known case vividly. Even though many decades have passed, his memories are still sharp. “O’Bryan adored the attention,” he said. “I think he even loved it during his trial.” Ronald of course entered a not guilty plea. His defense was putting the blame on some untraceable grump, who was using Halloween to poison innocent children. But O’Bryan’s family, friends, and coworkers testified against the man who was and is now known as the Candy Man. The trial was held on July 3, 1975, and it took a mere 46 minutes for the jury to give out a guilty verdict, which was well deserved according to the press. His charges were one for capital murder, and four counts of attempted murder for the other unsuspecting kids. And an hour later his fate was sealed, he would die by electric chair.

Even though there hasn’t been a case as dangerous and as harmful as the one explained in this article, there hasn’t really been anymore. During 2000 in Minneapolis, a man was charged for putting needles in the Snickers bars he had handed to the trick or treaters. The only victim he claimed was a teen who felt a slight prick from the hidden sharp object. Since the death of Timothy O’Bryan, there hasn’t been any case of a kid dying from contaminated candy received during Halloween.

After exploring all his appeal avenues, the only thing Ronald O’Bryan found were dead ends, as all his attempts were turned down. On March 31, 1984, he was finally put to death for his crime, after 10 years of being on Death Row. At this point, the US Supreme Court had decided that the electric chair was an abnormal and overall cruel punishment for all Death Row inmates. So his end came by a lethal injection of Euthanasia. Just outside of the Texas State Penitentiary in Huntsville, a crowd of about 300 people gathered eager to hear about the Man who killed Halloween’s death. They shouted “Trick or Treat” and threw candy at anti-death penalty protesters. At 12:48, Ronald Clark O’Bryan’s story had ended. Officer Hinton was in his childhood home in Amarillo, Texas. That evening he had gone to his favorite lake, had a fishing rod in hand, and drank in celebration of the greater good’s victory.