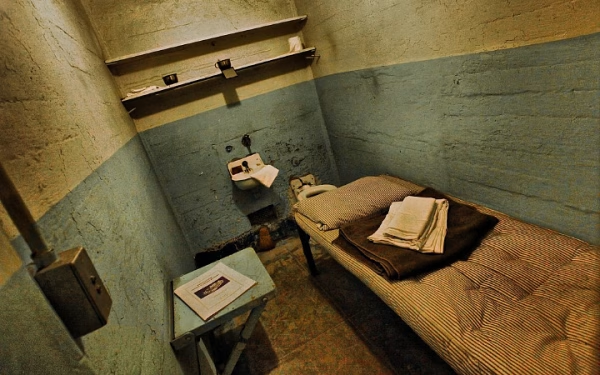

Whenever anyone thinks about some of the most protected, maximum-security prisons, many think about Alcatraz — a famous prison built in 1934. It was highly protected, considering it was located on an island with water stretching about one to two miles to land. Not only was it strongly secured, but it was also very costly to run. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, in their article “The Rock,” the cost to operate Alcatraz was about 3 to 5 million dollars per year, about $97,000,000 million today when adjusted for inflation. When the prison was active, many inmates attempted to escape but were unsuccessful.

But what made this prison so difficult to escape from?

Alcatraz held over a thousand prisoners. Who knows how many of them plotted to escape? According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, “36 men (including two who tried to escape twice) were involved in 14 separate escape attempts” (Federal Bureau). However, none succeeded. Out of the 36 inmates, 23 were recaptured, seven were shot and killed, and the others drowned.

But were there any successful escapes?

Now that’s a mystery.

On June 11, 1962, Frank Morris and brothers John and Clarence Anglin took their chance to escape. When the guards checked on them the next morning, June 12th, they were gone.

The burning question is: How did they do it?

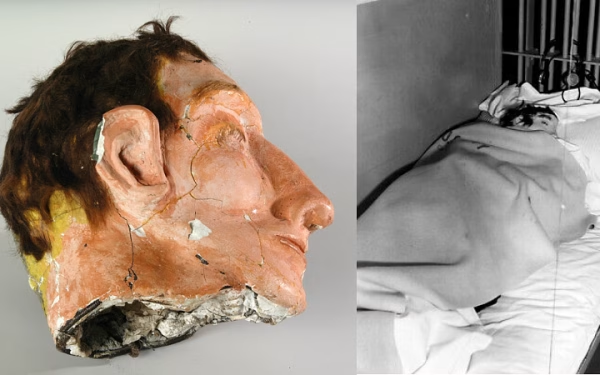

According to Britannica, in their article about the escape, it would have taken about six months of planning to accomplish what they did. For example, they made fake papier-mâché heads that they painted to make the guards think they were sleeping in their beds when, in reality, they were escaping. According to the BBC, “[they used] metal spoons purloined from the dining hall, a drill made from a vacuum-cleaner motor, and discarded saw blades [to] dig through to an unguarded utility corridor” (BBC).

They used the drill while other inmates played music, which helped cover up the noise. Frank Morris and the Anglin brothers also used papier-mâché and paint from the maintenance shop and barbershop to cover the chipping caused by digging out the vent. Because the guards rarely conducted thorough cell inspections, the inmates got away with it.

After making it through the vent, they climbed up pipes behind the cell walls to reach the prison roof. Once there, they slid down a smokestack to the ground. The final step of their escape was crossing the water. Over six months, they had collected more than 50 raincoats to create makeshift life preservers and a 6×14-foot rubber raft, according to FBI.gov: “[m]ore than 50 raincoats that they stole or gathered were turned into makeshift life preservers and a 6×14-foot rubber raft” (FBI.gov).

Swimming would have been nearly impossible due to the water temperature, which was about 13–15 degrees Celsius (55–59 degrees Fahrenheit). In addition to the frigid temperatures, there were extremely strong currents that could have easily killed them.

This escape remains a mystery because no one knows for certain whether Frank Morris and the Anglin brothers made it to the mainland. Anything could have happened during their ocean crossing — the raft could have sunk, they could have succumbed to hypothermia, or they could have drowned in the strong currents. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, “[t]he plan, according to our prison informant, was to steal clothes and a car once on land” (Federal Bureau of Investigation). If they made it to land, they would have needed to blend in quickly to avoid capture.

In the end, when people search for information about Frank Morris and the Anglin brothers, they find no clear answers. When they escaped in 1962, the FBI tracked them for years. After 17 long years, in 1979, they officially closed the case.

They made the silicone heads, made it past the vent, and built a makeshift raft. This was an incredible escape, meticulously planned for months.

They truly got away with it — if they survived.