History and Origins:

The sitar, an Indian musical instruments’ inventor, is credited to Amir Khusru of the 13th century, according to the “Sangeet Sudarshana”. Although sitars are mostly common in “[N]orthern India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh” (Britannica), there was a lot of Persian influence in the construction of sitars. For example, “there is a 3 stringed long necked instrument in Persia called the “setar or” three strings”…the modern sitar is some combination of the Persian setar, the tambur and the Indian Vina” (Musician’s Mall). There are actually 4 strings but the last 2 strings (The 2 closest to the player) are considered “one” since they both have the same purpose. The Persian setar helped influence the shape and appearance of the sitar as well. Although the “[d]ifferent sizes and design proliferated for centuries. The current “standardized” sitar is fairly new” (Musicians ‘Mall). This indicates that the sitar is constantly changing in its outward form. It has also been said that “[t]he modern sitar is an improved and modified form of the tri-tantri veena of ancient India.” (Singapore – National Library Board). This suggests that the sitar has been taking ideas and references of how the veena functions. The veena is a “large plucked lute that originated in the Indian subcontinent” (Romero).

The Construction of Sitars:

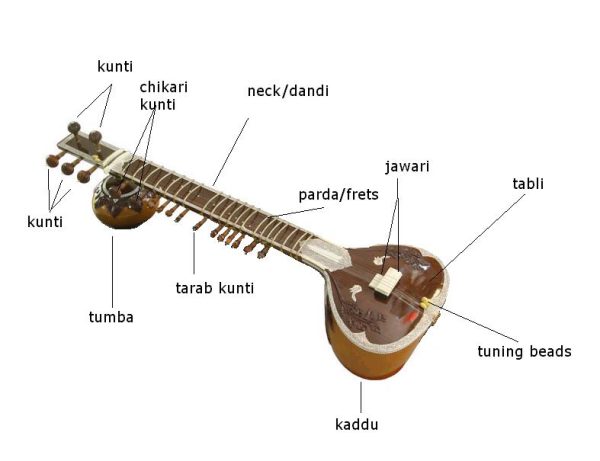

The very first step of the sitar-making process is the picking of the wood. Most sitar players, like Rajib Karmakar, say that they prefer teak or tun wood for their sitars. The main chamber is made of a very large gourd; this part is called tumba, which is then cut and reshaped. The front part, which sits on top of the tumba, is called the tabli. The tabli is cut from the desired wood and placed on top of the tumba. Next, the dandi, the long neck portion, is made by joining two pieces of wood together. The neck is then joined with the tumba with the gullu. The gullu is a small piece of wood that is placed above the tumba, connecting the dandhi. After all of the pieces are assembled, the desired decorations are then carved onto the sitar. Then, the last increment, the tailpiece or the langot, is installed. The langot is the piece that brings all of the strings together and tightly holds the strings.

After all of this, the instrument is then sanded for the perfect shape that is desired, sealed, and then coated with a finish (polish), French polish, that then dries over several days. After the polish dries, “the main tuning pegs (Kunti) are put on, and the main bridge is installed and shaped correctly (see Jawari). Then, the frets are tied on and correctly positioned to be in tune. Finally, the holes for the sympathetic pegs are drilled in the side of the dandi, and those pegs are installed” (Musician’s Mall). The kunti are the pegs that determine the sound the strings produce. The frets are the metal rods that are bent and tied securely to the neck of the sitar, and then the strings are tied together on top of the frets. One of the strings, usually the first string (the main string), is pressed down onto a fret and then plucked with a metal finger pick, a mizrab, to produce sound. Depending on the position of a fret, the sound can be different. When the fret is moved, the sound that is generated will change.

Notable Sitar Players:

Many excellent people strived in sitar, such as Ravi Shankar, Imrat Khan, Anoushka Shankar, and many others. First and foremost, Ravi Shankar was well known for his amazing talent in sitar. Ravi Shankar is still today “…one of the most renowned sitar players and a global ambassador of Indian classical music” (Webster). Ravi Shankar is widely known for helping promote Indian classical music and the sitar to the world. He collaborated “with Western artists and introduc[ed] the sitar to new audiences worldwide” (Webster). He is also known for teaching George Harrison (now dead) from the Beatles how to play sitar. Moving on to Vilayat Khan, he was “[r]enowned for his innovative playing style and emotional expressiveness…” (Serenade Team). The contributions to the sitar’s technique and repertoire that Vilayat Khan made were quite significant as well. There are a lot of well-known and influential people regarding the sitar, but the last influential person who has reached great heights is Anoushka Shankar. “Continuing the legacy of her father, Ravi Shankar, Anoushka Shankar has become a prominent sitarist in her own right”(Serenade Team). Just like Vilayat Khan, she has also expanded the sitar’s repertoire by mixing traditional Indian music with other kinds of genres.

What Materials Do Rajib Karmakar Think Are the Best for Sitars?

After an interview with Rajib Karmakar, a professional sitarist, composer, and musician, he says that Teak and Cedar are his top picks of wood. He says this about Teak wood, “[i]t was previously used because it would last for a long time, about 40 years, but the bad part is that it is heavy”. After some debate, he picks Pyramid or Roslau as his favorite wire type. One big question that comes up is: Why are there different types of sitars? Rajib says, “Every sitar has a different amount of strings. This also may be due to the differences in the styles of sitar or even the tonal quality of it.” Sitars can also have different shapes due to the Kharaj Pancham and the Gandhar Pancham. These refer to the different styles of sitar that can be found.

After learning about this stringed instruments’ aspects, they seem to play a crucial role in Indian culture. It is quite certain that the sitar will continue to evolve and change the way people look at sitar forever. Sitars are constructed in a specific way that helps it create a certain sound that is both magical and elaborate. The product of the sitar evolved from the Persian “setar” and the [Indian] veena, but it has its own characteristics that make it unique. This wonderful instrument featured in the article is a traditional Indian stringed instrument known for its distinctive resonant sound, played with a mizrab, and featuring a long neck, a rich, melodic tone, and sympathetic strings.

This article was possible thanks to the following sources:

Musician’s Mall- Sitar String Instrument: History Construction, Jawari, and More

https://www.musiciansmallusa.com/overview-of-sitar/?srsltid=AfmBOoq7QBw4AisGPQHwIXeg6rMKQjGzi5LT0o_V34V32r70cVZde1A-

Sitar | Definition, Description, History, & Facts | Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/art/sitar

Sitar – Singapore – National Library Board

https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=ff4639e1-f8b6-4217-9559-877b2531fe2c#:~:text=The%20modern%20sitar%20is%20an,later%2C%20another%20string%20was%20added.

World Music Central – The Time-Honored Veena of India | World Music Central

https://worldmusiccentral.org/2023/11/02/the-time-honored-veena-of-india/

Introduction to the Sitar: An Icon of Indian Classical Music – Serenade Magazine

https://serenademagazine.com/introduction-to-the-sitar-an-icon-of-indian-classical-music/

10 Famous Sitar Players – Mixing A Band

https://mixingaband.com/10-famous-sitar-players/

INTERVIEW WITH A PROFESSIONAL SITAR PLAYER

Rajib Karmakar